Color Spaces¶

First off, what is the difference between the sRGB and sRGBLinear color space? A color space is defined by two factors, its Primaries and its Transfer function.

Primaries¶

The primaries refer to the most red or most blue a color can be. The chart below is called a CIE chromaticity diagram, and it represents all colors (but not intensities) visible to the human eye.

The black triangle is the number of colors available to sRGB, and the black points at the corners of the triangle are the primaries. The bigger the triangle, the more colors are available. Larger triangles are sometimes referred to as wide gamut, or as having larger primaries.

When comparing sRGB and sRGB linear the two have identical primaries, thus any color in sRGB can be expressed in sRGB linear and vice versa.

Transfer Function¶

Where sRGB and sRGBLinear differ is their transfer functions. If the primaries tell the display “what color should this be”, then the transfer function tells the display “how bright should this be”.

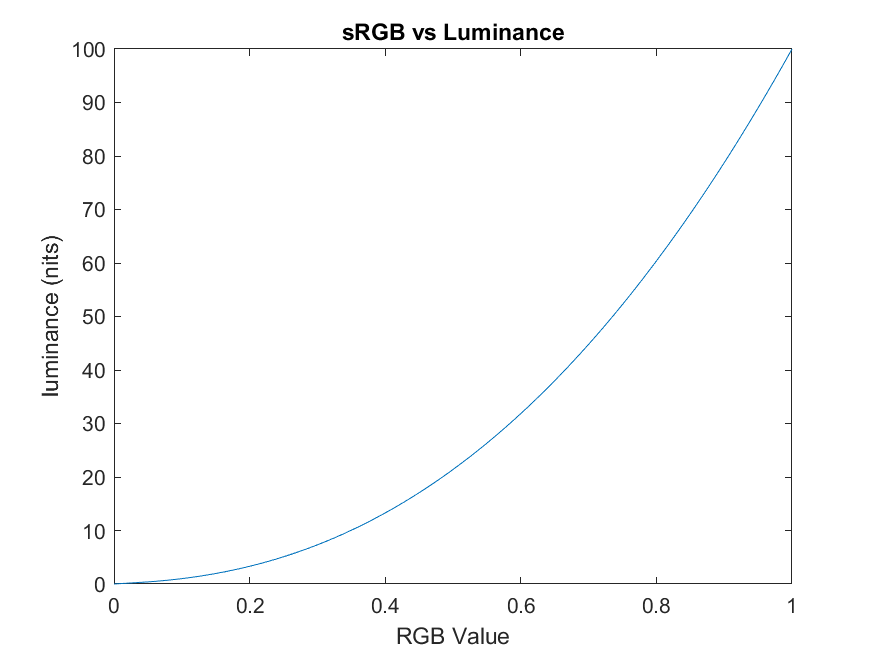

For a display capable of showing up to 100 nits of brightness, the sRGB transfer function should look like:

Thus, if you wanted to display middle gray which should have a luminance of 18 out of 100, then your sRGB file needs to have values [0.36, 0.36, 0.36].

The above graph doesn’t tell the whole story, or even the most important point. In reality there are not infinite values which r, g, and b can take on within a file. For an 8-bit file format, such as .png then each color channel can have 256 colors. Having a limited set of colors is where transfer functions come in handy.

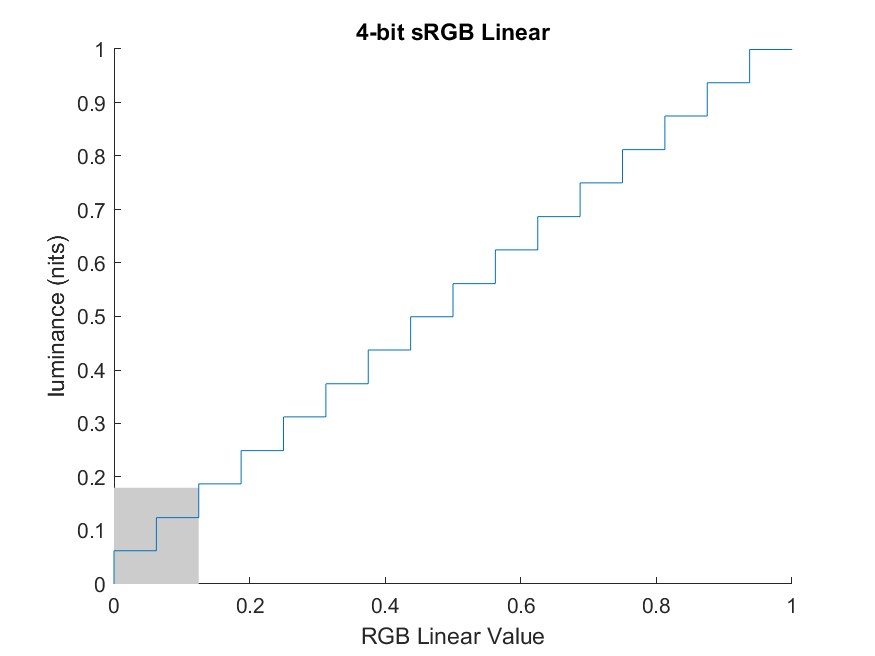

To illustrate the above, let’s look at an example using only 4-bits to encode our sRGB luminances, and consider only a single color channel. We divide the x-axis into equal sized buckets, then our graph becomes:

The gray square represents everything up until middle gray. Middle gray is important because most people perceive middle gray as halfway between white and black. About 35% of the buckets are able to store values below middle gray.

In contrast, let’s look at the same 4-bit image but with a linear transfer function:

Notice fewer buckets are available for values below middle gray, only 18% of the buckets are available to store shadow information.

Let’s have a look at some images. Here is an sRGB image from dark to light that has been squeezed into 4-bits using the non-linear sRGB transfer function.

The horizontal-spacing between vertical bands is unimportant, but pay attention to the difference in darkness between each band. We perceive the difference between each band as roughly equal.

By contrast, here is the same original image squeezed into 4-bits using the linear sRGB transfer function. (The final image has been mapped back to sRGB in order to display correctly on a monitor.)

Notice that the dark areas are less detailed, while the highlights have much more detail. We also perceive the jump between bands as non-equal. The difference between the darkest and second-darkest band feels more dramatic than the difference between the two brightest bands.

If you’re still not convinced, compare the same example image but against slowly increasing bit-depth.

Notice that the sRGB image “converges” faster. A 6-bit sRGB image gradient looks smoother than the 7-bit linear sRGB image. Thus if you want to save space but keep the image looking the same then use a logarithmic transfer function.

Pretty unexciting right? That’s exactly why linear is preferred by the VFX industry, and is used by ACES. If you double a linear value, the brightness doubles. This is not true of sRGB or any other non-linear format.

If linear is so great, then why do we use nonlinear?

Non-linear is less expensive, at least when it comes to sending video to consumers. Linear generally means larger files, which are more expensive to store, transmit, and decode. It’s a trick to allocate more space in the file towards things humans will notice. One could say that our brain sees light non-linearly.

In fact, non-linear started well before digital video. It’s so common in consumer devices that all consumer cameras output nonlinear signals, and all consumer displays expect nonlinear signals.